Alexander and the Pursuit of Beauty

14th March 2018, revised May 2024

View a printable PDF of this Article

Let it be anything you like but at least let it be unified

—Horace, the Art of Poetry

For a long time I was involved in furniture making and design and it felt natural to relate what I was doing to the Alexander principles which underlay the rest of my life. There’s been a lot written about Alexander in relation to more spontaneous creative pursuits—music, dance, acting, etc.—but not so much in relation to making and craft. I suppose this is because Alexander seems more obviously applicable to activities where the artist ‘kisses the joy as it flies’—were the work is produced in real-time, directly from the activity of the Self. A pianist plays and there is music; a dancer moves and there is dance. Craft, on the other hand, tends to be slow, and demanding in a different way. Any sense of artistic accomplishment is experienced only in fleeting moments during a long, laborious making process. Hopefully, if things have gone well, it will come in greater fullness when the work is complete.

So how can Alexander Technique principles help us in this kind of time-extended pursuit? I’d say in four ways: they can help us work healthily and safely and to wield tools skilfully; they can open up questions about process, ends and means; they can give us an approach to revealing beauty suggested by inhibition and direction; and they can help us to attune to the qualities of life, movement, delicacy and strength which are the hallmarks of beautiful work.

Working Skilfully

People often imagine furniture making as being a romantic thing but it isn’t really. It’s physically demanding, dusty, often noisy, occasionally frightening (big machines can easily kill or main) and repetitive. In addition, if we are starting with rough-sawn timber there are considerable weights to be moved around the workshop, so to make anything with a degree of efficiency you first have to be in good physical shape. The Alexander Technique can certainly help us maintain this in the face of the demands the work puts on the body. We can also note as a matter of course that it can help us master the more refined parts of the process, teach us to use hand tools well and to handle them with the delicacy and refinement needed to do high-quality work.

Woodworking can be stressful—particularly as we near the end of a long project when the costs in time and labour embodied in the piece have become quite high. There's the stress of worrying about making ends meet (this is a high overhead business), about disappointing customers who are paying a lot of money, and about mistakes which can be very expensive. Alexander principles can help us to manage stress and to keep calm when everything seems to be going wrong. It can help us to have the sense to ‘stop’ and take a breather—not only when we are getting into a mess, but also when things are flowing suspiciously well which, paradoxically, is often the time when mistakes are made and accidents happen. There’s nothing more illusory than the feeling of invincibility which comes with flow. A pianist may play a wrong note: a cabinet maker might lose a finger. There’s no space for Dionysus in the workshop.

Beyond the Mundane

However valuable such mundane, everyday considerations about efficiency, safety and practical skill may be, more interesting from a creative point of view are the considerations of ends, means and process that Alexander work encourages.

Industrial-scale woodworking, for example, is of necessity very ‘ends’ focussed. Considerations of efficiency and utility rule. How the final result is achieved is predicated largely on cost. Tooling, techniques and workflow are usually based on speed, with little consideration for how they affect the feel of the final piece, which is produced from an image in the head of a designer who could be on another continent. The result is often a dispiriting uniformity and soullessness (although we can’t really deny the logic of mass-production if we live in an over-populated world and hope everyone will be well-fed, housed, and have a bed to sleep in).

As we get to the finer, more bespoke end of things, though, where people may be prepared to pay more (by necessity a lot more) for something special and unique, other considerations come into play. We might realise that the need to charge so highly for a piece of furniture has to be justified, and one way to do this is by thinking about the possibility of much greater complexity and richness of ends, and about what means might be needed to get us there.

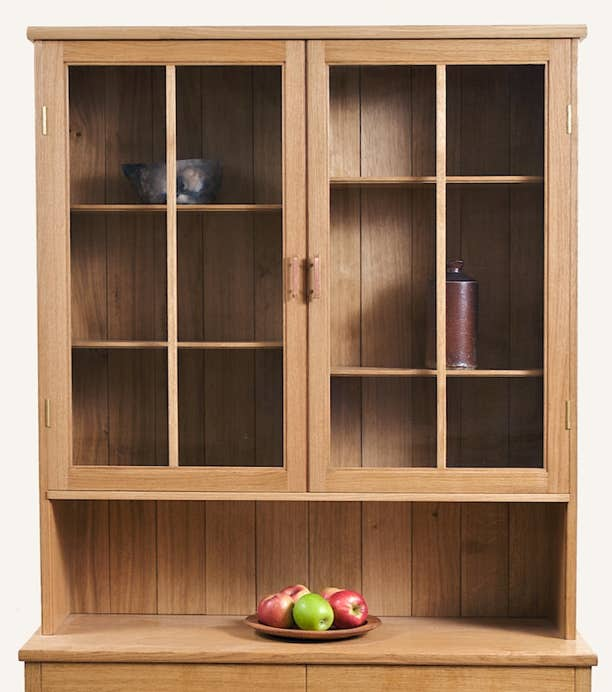

We may start thinking, for example, about what might benefit people in a deeper sense than simply owning a useful or attractive item—such as the need for a sense of beauty, place and connection to history and the world around them. Looking around us we may start to see that the sort of things that meet these needs in a deep way tend to have certain qualities, including a feeling of connection to past and present (timelessness); a sense of life which reflects the natural world and helps people feel connected to it; diversity (the shimmering quality which appears when there are complex layers of detail that go ‘all the way down’); a tangible (literally ‘touchable’) sense that the maker cared about what they were doing and the people they were making for; and a pleasing engagement with many senses—obviously visual, but also texture, sound and smell. Does it matter how a door clicks when it closes? Does it really matter whether or not we make our draw bottoms from cedar of Lebanon to give a lovely piney smell whenever they are opened? Of course it does! And amongst all this we may also wish to find an ‘ascending’ quality, a sense of movement upwards to remind us that we are spiritual beings (whatever that may mean to us) as well as a sense of downwardness, a rootedness to the earth that is our home.

Something we may notice as we start to think like this is we are no longer in the realm of quantity (units sold, functional items acquired). We have moved decisively into the realm of qualities, and this brings us firmly into a sphere where Alexander becomes relevant because the ‘goals’ in Alexander work are also about qualities. There is no ‘right position’, nothing that can be measured or set in stone, or produced by doing something predictable. There are instead desirable qualities which we can allow to manifest or become aware of. ‘Up’ is a quality, not a position. ‘Free’ is also a quality, as is ‘open’, ‘expansive’, ‘grounded’, ‘present’ or any of the other myriad indicators of ease and good use. Such qualities can’t be tied down in quantitive terms, because they have a living, evolving connection to the moment and are never quite the same twice. There is no formula for them: either they are present or they are not.

One of thing the Technique teaches us is that to experience such qualities we need to let go of our obsession with ends, and attend to the process which takes us towards them. Implicit in this is that the qualities we end up with are inseparable from the process by which they are arrived at. The ends and means are, in a sense, one thing. So if we want to be making pieces of furniture, or pots, or textiles, or any other beautiful thing which reflects worthwhile qualities, we’d better be thinking about the way we intend to get there as well as the destination.

Something we can notice about the list of qualities I suggested—timelessness, beauty, life, rootedness, diversity, upwardness—is that if we are to express them all together in a piece of furniture we are involved in a complex undertaking! It’s a tall order to manifest many of these qualities in a single piece. In addition, we are working with wood, and wood is not uniform—each piece is different, and differences in grain and pattern will make two identically sized pieces look and feel very different, adding another level of challenge. A door which looks balanced and harmonious with one piece of timber may look all wrong with another, though the dimensions are identical. We have to balance differences in grain so everything comes out harmoniously. And in spite of this complexity, what we need above all is for the different qualities we are working with to hang together into a whole. If we are to produce something to lighten the heart we need the end result to have a sense of integration.

A helping hand in all this is that furniture is primarily functional. We are not making a piece of art but something which first has to perform its job, and this puts limits around what we are doing and sets a clear direction. If we are making a chair it must be comfortable and strong before it is beautiful. So what we are doing has bounds, and those bounds are our starting point—just as if I am intending to get up from a chair without unnecessary stress or strain, those bounds give me a general intention around which I can organise what I’m up to. From there I can start to wonder about the process needed to achieve it.

So what sort of process will help us to end with a piece of furniture with a sense of soul and life to it? There’s no formula to help us. We’re dealing with a unique problem—a piece for certain unique people to go in a certain place and perform a certain function, made from unique materials. It can’t be quite the same as anything else we’ve done. Once I made the mistake of creating an exact copy of a piece I was rather proud of. The original had a certain quality of life, I thought, but the copy was dead on arrival. The process that had lead to certain dimensions and decisions with one load of timber was a unique response to that particular batch. So even if we are making something similar to a thing we have made before, we know we will need to be producing something to some extent new—something currently unknown with its own qualities of life, movement, balance, groundedness, history and ascent.

What might allow us to approach this problem effectively? Firstly I would say we need to find a way of working that allows a dance between the qualities we want, and an awareness of what is not them—of what is preventing them or getting in their way. This sounds a lot like what Alexander teachers traditionally call direction and inhibition. At the same time, we will need a way of working that allows this, while also allowing us to move from the known to the unknown enabling something new and unexpected to come about. We mustn’t nail everything down from the start in a rigid plan. We need to find a way of working with wood that's structured enough to meet the practical demands of the piece we are making while also leaving space for responsiveness as we go.

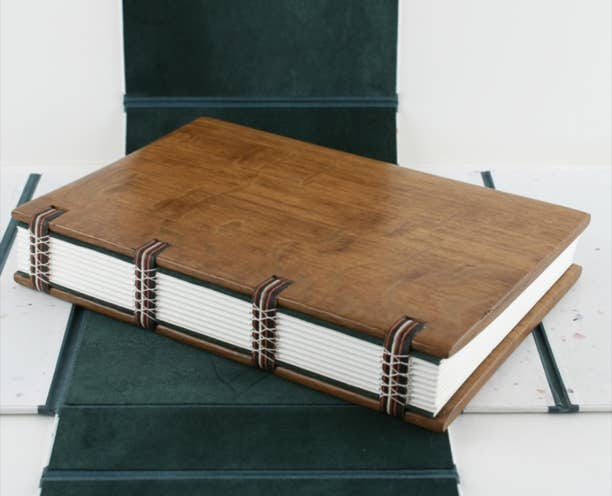

One way to approach this is to feel our way delicately towards the result we want through a process master cabinet maker James Krenov called ‘composing’. This means working without any drawings and only an idea of the structure in our head. We let the design and precise dimensions evolve through working with increasingly refined mockups made, as much as possible, from the actual timber we are using. This leaves a great deal of freedom with room for spontaneity and serendipity. If the design is complex, though, or involves mechanisms of any sort, then the difficulties of keeping track of what we are doing can easily lead to mistakes. In this case a halfway-house is to use what I call an ‘open drawing’ (this could be a scale drawing or a full-sized ‘rod’) in which key dimensions are fixed, but as much as possible of the detail is left only roughly sketched and filled in as we go. Either of these approaches gives us a flexible general intention within which we can allow something fresh to arise.

Working this way allows a constant interplay between what we see and feel, the qualities we are looking for, the limits and possibilities of tools and techniques, and the qualities of the timber itself. Instead of a dry process in which we are exactly reproducing a pre-existing plan, there’s an element of life and spontaneity in what we are up to, even at the glacial pace enforced on us by hand-crafting a resistant material. Rather than working only from a visual image born in our head without reference to the actual material to be used we are allowing our hands, our fingertips, and our sensitivity to living form to enter into the equation. At every step there’s room for a spark which can make things happen.

Direction, Inhibition and Process

How can we use this freedom we have given ourselves to help bring about the qualities we are looking for, and to integrate them into a piece that has a feeling of unity and wholeness about it? The concepts of direction and inhibition are surprisingly helpful here. We have a direction, or many directions, that refer to qualities which need to be present, ‘one at a time and altogether’. We want a feeling of life, of history, of ascent, of timelessness, of complexity and diversity, all tied together by a feeling of unity and integration. These ‘wishes’ for our piece are like directions. And, as with directions, all we can say for sure is what is not that. We may make a move in our mind which feels right, or start to plane a delicate profile on an edge but must always be asking, ‘is this taking the piece towards the qualities we want or is it not?’. Is our excitement about our idea for a part contradicting some deeper wish we have for the piece as a whole? If so, we’d better stop and try something else.

‘Like this?’

‘No, that’s dragging it down’.

‘This way?’

‘No, it’s becoming rigid’

‘That way?’

‘It loses its connection to the ground’

‘How about….’

‘Ah, I can go with that…’

This way of working can be rather arduous, involving as it does an almost continuous process of saying ‘no’ to any possibility the mind or body is drawn towards that contradicts the qualities we are after. Day after day, week after week, until the piece is finished. It takes a lot of discipline. Wood is beautiful, and tools and techniques can be compelling. Sometimes we have an idea that's so lovely in its own terms that it’s hard to say no to it. But of course, that’s what art is about—‘killing your darlings’. And killing your darlings is a form of inhibition. It’s about noticing what is not good and

saying no.

This kind of sensitive, exploratory, negative process was very much a part of the way humans worked with wood before we had standardised working practices and machines. Planking up a clinker dingy, for example, involves putting on each new plank alternately across the boat and sizing up by eye whether it looks balanced with the ones that are already there. You are asking ‘what needs to be taken away here’, and you remove material until it looks right. The end is a kind of live, simmering quality which is quite different to work made with mechanised techniques. It’s not perfectly symmetrical, but it’s more beautiful for that.

When we’re creating furniture in the way I’m describing, saying ‘no’ to the wish to prematurely cry ‘to hell with it, it’s done!’ is often the hardest part, especially if there are impatient customers waiting. ‘They won’t notice this little detail—this little reveal or that subtle lift of a rail’ we tell ourselves. And the thing is, often they really wouldn’t. Many of the details we do in this kind of work are subliminal. They’re often not usually registered consciously by the observer at all. But make a piece without any of them and sure as hell they’d notice. Individually, details can seem like a chore. Together they’re the difference between—as craftsman David Pye puts it—‘a piece that sings and one that remains forever silent’. So we’d better take the time if we care about the difference.

The World in Ourselves

Of course a piece of furniture is not really alive: it doesn’t actually sing, and it is not really even unified in the sense a human, plant or animal is. It’s a collection of bits screwed, glued or jointed together with no meaningful relationship between them except in so far as our mind creates one. So there’s a bit of an illusion about all this. But it’s a good kind of illusion which tells us something about ourselves. There’s a quality I see in myself that's indicative of the life in me. For example I might notice how I walk or dance with an easy rhythm which is regular, but not rigidly so. So I take this to my cabinet or dresser or whatever it is, and I create rhythm with the drawers or the doors or some other subdivision that is also regular, like walking or dancing but, also like those things, not rigidly so. There may be a gentle expansion or contraction of the interval between regularly spaced elements, or they may be spaced with subtle irregularity. And this, like the irregularity woven around a good drummer's pulse may be so slight it is perceived only subliminally most of the time.

Or I see that, like any part of nature, I don’t have perfectly straight lines in me, but I do have lines, for all that. So I might reflect this in the lines of the piece which are given gentle lifts or flowing profiles carved or planed by hand which may again be so slight as to be subliminal but which belie and soften the Apollonian geometries and ratios that link the piece also to the world of human thought and can be related in some small way to some 3000 years of human culture.

One is helped in reproducing such qualities by the extent of the sensitivity one has access to, and the depth with which one has met them in oneself. How deeply does one know the delicate strength in one’s body? How intimate is one with the irregular-regular rhythm of one’s own free dancing or walking? It is this strange relationship between oneself as a living, breathing being and the hard, unyielding, demanding wood which is part of the fascination and frustration of working in such a slow and laborious medium.

Ultimately, the slowness and the laboriousness, the dust and the noise, and the relentlessness required to consistently earn a worthwhile financial return, eventually caused me to stop making furniture, at least for money. One of my favourite tools—a little beech bollow plane I made myself—sits on a shelf above my desk. Now and then I look up at it and feel surprised I started such an enterprise and surprised I stopped. It feels like a loss, though the opportunity in the space this decision opened up is also great. But in so far as the process of making grew from a consciousness about ends and means and saying ‘no’, and in so far as the work does indeed reflect some kind of feeling of aliveness in myself and the world around me, I like to think that the hands of those who have worked with me, and of those with whom I have worked, also have their own subtle reflection in those pieces, and will live on for a while in the best of what was made….

Copyright © 2018, 2024 Marcus James